|

| 90% partial eclipse. Photo by Fred Espenak (NASA GSFC) |

What's happening, when, where?

This table shows when the eclipse is happening, and how much of the sun will be eclipsed at maximum, at a number of location around the UK. You'll see that, the further north and west you go, the better the eclipse. Unfortunately, nowhere in the UK will experience totality. For that, you'd need to go to the Faroes or Svalbard.

|

| Eclipse predictions by Fred Espenak and Chris O'Byrne (NASA GSFC) |

You can get predictions for any location you like on NASA's incredible eclipse website, here:

http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/JSEX/JSEX-index.html

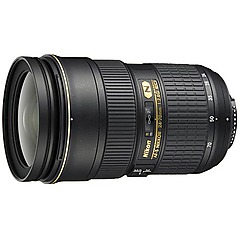

What kind of lens do you need?

In short - a big one. The biggest one you can lay your hands on, and then a bit bigger. The sun is so bright, it's easy to overlook the fact that it's actually quite small. Here's a simulation of what you can expect with various lenses of different focal lengths.

How do you photograph the sun?

You need a very, VERY dark neutral density (ND) filter. NEVER look directly at the sun through a camera lens. Remember, the sun might be 90% eclipsed, but the bits that aren't eclipsed are just as bright as usual, and that can really damage your eyes.

Trouble is, the terminology used to describe filters can be confusing, and manufacturers and retailers aren't consistent. There are three different ways of describing the strength of a filter which are in common use:

- The multiplier for the exposure

- The number of stops effect on the exposure (every stop is a doubling)

- The multiplier for the exposure expressed as a power of 10.

So for example a "3x" filter could mean that it makes your exposure 3 times as long, or it could mean that it increases your exposure by 3 stops (8 times as long). Similarly, a filter described as "ND3" could increase your exposure by 3 stops (8 times as long) or by a factor of 10^3 (1000 times as long).

Here's a quick reference, based on these three different scales:

It's VITAL to understand what any given filter is actually doing, before you put it between your eye and the sun. If in doubt, ask and ask again. If still in doubt, don't do it.

But anyway, now we understand what filters do, how strong a filter do we need?

In general, you probably want 12 stops or better. The gold standard for specialist solar filters is Baader Astrosolar safety film - http://astrosolar.com/en/ - and they make it in two flavours. ND3.8 (12.6 stops) is designed for photography, and ND5.0 (16.6 stops) is recommended for visual observation. If you put a 10-stop filter, or a filter made of ND3.8 film, on the front of the lens and look through the camera wearing dark glasses, you'll probably be OK - but don't blame me if it ends in tears.

You can buy strong ND filters, but they're quire expensive. For example a 10-stop screw-in filter, in the commonly used 77mm size, costs around £80-£120. If you have a square filter holder, a 10-stop square filter costs about the same. Alternatively you can buy Baader film for about £20 per sheet and make your own filter - there are plenty of instructions out there on the internet. Or some people would even advocate using welder's glass, which is very cheap, and can be very dark - but if you do, make sure you test its strength first.

Apart from getting the right lens and the right filter, photographing the eclipse is going to be quite easy. You won't need a tripod - unless your lens is too heavy to hand hold! - because, even with a strong filter, you'll be getting very fast shutter speeds. For example, the other day I did some tests with a 13-stop filter. I was getting 1/2000th at f/16, 100 ISO. So that's comfortably within the range of any DSLR. All you need to do is dial in a suitable aperture and/or shutter speed, focus your lens on infinity, set the camera to spot metering, point, shoot, and repeat as desired. If your filter imparts a colour cast, it's easy to fix it in Lightroom or Photoshop afterwards. Job done.

Let's do it!